“This day in history”: 45 years since the Edmunds Fitzgerald

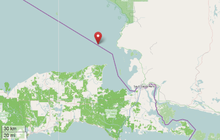

Map of where the Edmunds Fitzgerald sank.

October 11, 2020

It’s been 45 years since the Great Lakes’ most tragic event. On the night of Nov. 10 1975, history was to be made. As the Edmunds Fitzgerald served her time hauling tactone iron, she was the largest freighter on the lakes, given the title “Mighty Fitz,” or “Queen of the Lakes.” This night went down in history; not only did the Fitzgerald go down, but so did 29 brave men. This November will mark the anniversary of Michigan’s most memorable lake accident.

The roars of huge waves and striking sounds of thunder confirmed a storm was making its way through Lake Superior. As all ships were given the red flag, Captain Ernest M. McSorley was determined that his ship, The Edmunds Fitzgerald, was bound to survive this atrocious storm. While further ahead the Arthur M. Anderson that day, both freighters kept within a 10 to 16 mile radius of each other in case something were to happen. Little did they know, the Fitzgerald was in trouble.

Shortly after 3:30pm, the Fitzgerald reported to the Anderson that when taking on waters, the freighter had lost two vent covers and a fence railing. Nearing Whitefish Point, both freighters were highly pressured to dock at any nearby port. It was crucial that these freighters put a halt to their voyage. Either way, there was no getting through to Lake Huron because of the Soo Locks being closed. With the Fitzgerald and the Anderson staying in close proximity, they both were recording high winds of 50 knots (58 mph) with gusts of 70-75 knots (81-85 mph). Waves were anywhere around 35 feet as well; putting this into perspective, dangerous boating and swimming is considered three foot waves, and when a coast guard calls a red flag, this indicates waves over eight feet.

At approximately 7:10pm, the Anderson notified the Fitzgerald of a ship coming upbound. The Anderson asked how things were holding up, and the captain of the Fitzgerald replied to the Anderson, saying, “We are holding our own.” Those were the final words to ever come out from the Fitzgerald. Due to the storm, many radios were not in program, and others were struggling to keep a connection. The Anderson finally connected with the USCG in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, keeping its emergency channel open, but there was no sign of the Fitzgerald. Expressing more concern, the Fitzgerald had officially been reported missing at 9:03pm. With a serious accident surfacing, the USCG asked for the Anderson to turn around and look for survivors. Around 10:30pm, any vessels docked near Whitefish Point were asked to help search for the Fitzgerald. With no luck, The Traverse City, Michigan USCG station launched a HU-16. During the three-day search, they only recovered lifeboats and rafts, but no crew members.

On November 14th, 1975, the wreck of The Edmund Fitzgerald was found 15 miles from Whitefish Bay. When the Navy dived on the wreck from May 20th- 28th of 1976, they found the Fitzgerald lying in two pieces, similar to The Titanic. The Fitzgerald does not live alone; between 1816 when the Invincible was lost at sea on Lake Superior, and when the Fitzgerald went down in 1975, there lies approximately 240 other wrecks in the Whitefish Point area.

The Edmunds Fitzgerald, along with many other lake freighters, hauled tactone iron most frequently to and from Superior, Wisconsin, and Detroit, Michigan. Many conspiracy theories have materialized due to the fact that there is no evidence indicating how the ship sank, and there were no survivors. It could have been the storm, how much iron the Fitzgerald was hauling, possible damage before setting out, etc. 45 years later, the Fitzgerald still remains the most famous, and largest freighter, to sail the Great Lakes in its time. The nickname “Mighty Fitz” originated from its size of 730 feet long, and mighty ability to carry 26,000 long tons. The Fitzgerald’s record load was 27,402 long tons, just for a single trip. The Edmunds Fitzgerald earned her name from chairman of the board at Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance company, which built this $7 million beauty ($49.7 in 2019 dollars). Edmunds Fitzgerald, the man who the lake freighter was named after, came from a long family line of lake captains. He was bound to have one in his name— he owned the Fitzgerald, after all. Covering more than a million miles, the “Queen of the Lakes” completed an estimated 748 round trips, equivalent to 44 trips around the world. Captain Peter Pulcer was in charge of the set cargo runs, and he was best remembered for “piping music day and night through the ship’s intercom system” when passing through the St. Clair river. When going through the Soo Locks, Pulcer would often times come out of the pilothouse and use a bullhorn to entertain tourists.

In 1995, the Edmunds Fitzgerald’s bell was dived on, recovered, and is now held as a memorial in Whitefish Point’s Shipwreck Museum. As a token of remembrance, Gordon Lightfoot wrote a six-minute and 40-second song on the importance of this night. Every year, not only does the Shipwreck Museum hold a memorial ceremony, but so do others. At the museum, they ring the recovered bell 29 times in honor of the 29 men that were lost, but never recovered. Other ceremonies set out 29 roses for those men, display the bow anchor that was lost in the Detroit river, or display lifeboats that were lost. These places also hold a Lost Marines Remembrance each year.

It’s been 45 years since this tragic event, and the Edmunds Fitzgerald has its 45th year at the bottom of Lake Superior, accompanied by many lost and found wrecks. Lake Superior may never give up her dead, but that doesn’t change the importance of these 29 brave men and the importance behind this night.