Black Lives Matter: A community divided

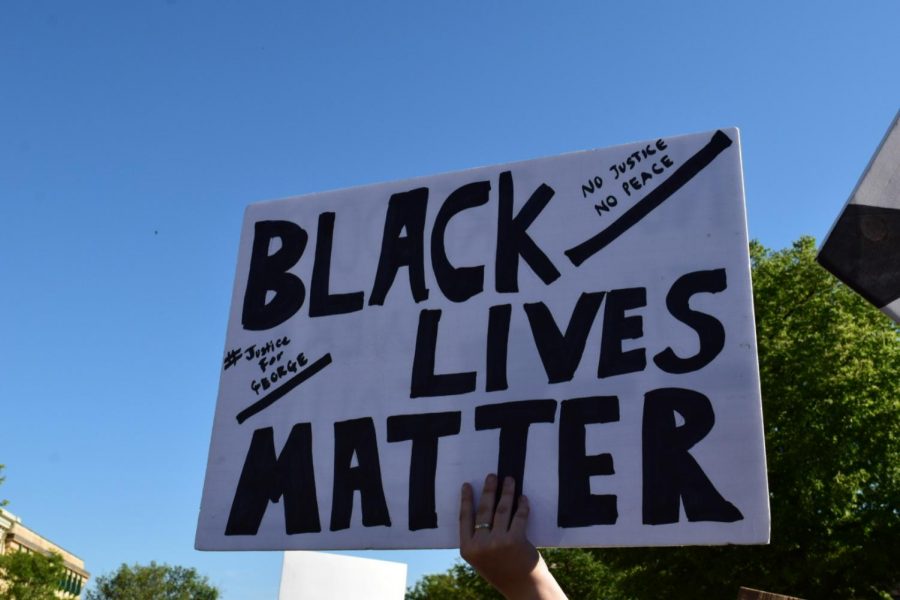

A person at the Black Lives Matter protest in Milford, MI holds up a homemade sign.

September 25, 2020

Milford, Michigan is a relatively unassuming town. Many of its residents enjoy its tranquility and comforting suburban bliss— but on June 8th, 2020, it was one of the loudest towns in the state. The downtown area, often moderately busy, was packed full of men, women, and children. They marched through the streets, listening intently for just one repeated call of many from the front of the crowd: “Say his name!”

Hundreds of voices cried in response, “George Floyd!”

This didn’t just happen overnight.

Since late May 2020, Black Lives Matter has been making headlines all over the United States along with images of protests, counter-protests, burning buildings, police officers clad in military gear lined up single file, and tear gas canisters thrown onto city streets. Some view Black Lives Matter as an organization and a social movement with a meaningful message, while others view it as a threat to national security. But what is it, exactly?

Black Lives Matter initially began as a hashtag. In 2013, after the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s killer, George Zimmerman, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi coined #BlackLivesMatter on Twitter. It quickly gained traction, and soon after, the three women rallied together several other activists to turn Black Lives Matter into a formal organization. Its goals are listed as follows: “to eradicate white supremacy and… intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state.”

Whenever an act of police brutality is committed, the phrase Black Lives Matter is sure to appear. It has developed into more of a rallying cry, seen on virtually every social media platform, shouted at protests, painted on buildings, and even sold on T-shirts.

The example of George Floyd is a pertinent one; after he was killed by police officer Derek Chauvin, many people expressed their anger in more ways than one. In Milford, opinions have split both ways, with some people proudly proclaiming support of Black Lives Matter— and others not wanting to associate with it at all. Milford High School’s student body is no exception.

MHS senior, Joe Antrim, says that he supports the movement out of a sense of moral obligation. “I feel like it’s my responsibility to… I see these stories of, you know, this man like George Floyd who committed a crime that’s punishable by a fine or maybe short jail time, or Breonna Taylor who was in her own home— and she didn’t even commit a crime— and they were [both] killed on the spot.”

MHS junior, Julia Kanak, shares a similar sentiment: “A movement designed to call out racial injustice in our corrupt nation is a necessity. People of color are exhausted from centuries of mistreatment, and as a white person, I acknowledge my role in their plight and know I must do more to make things right. We live in an era where our voices make all the difference.”

While support for Black Lives Matter is widespread, so is its opposition; phrases such as “All Lives Matter” or “Blue Lives Matter” have cropped up in response to the hashtag-turned-organization-turned-social-movement. Those that do not support it cite a plethora of reasons: some feel that the movement is too violent, given that some protests have turned into riots (although it is worth noting that over 93% of protests were peaceful), while others, like MHS graduate Jake Miller, feel that there is “no systemic racism in America, or in the police, for that matter.” Some even feel like the movement is contradicting itself. Another MHS senior, Kayla Kotas, agrees: “I think that Black Lives Matter has the goal of making all people equal, which I stand for, but sometimes I think some other things they stand for, like how they think all cops are the issue, just isn’t right. It’s hypocritical.”

In Milford, Michigan, it’s not hard to find ideological differences between a person and his or her next-door neighbor. Thus, it was incredibly surprising, even to Black Lives Matter’s supporters, when word of a protest began to spread— a protest right in the front lawns of many residents, organized in part by Megan Swirczek, who graduated from MHS in 2017. The reason she organized it? “Milford is, I think, 96% white… Towns that are predominantly white need to have these conversations. Think in terms of lack of exposure— we haven’t [had enough exposure] to talk about it… It’s not enough to not be racist. You have to be anti-racist. Actively.”

Clearly, enough people agreed with this sentiment; shocking even Swirczek, several hundred people marched, some Milford residents, some not. Some estimates have even guessed that around five hundred people were in attendance. Chanting things like “no justice, no peace”, George Floyd’s name, and Breonna Taylor’s name, the crowd was certainly difficult to ignore. They stretched through downtown Milford end-to-end, receiving applause from some spectators and booing from others. At one point, they even managed to stop traffic to kneel.

The Black Lives Matter organization has listed its goals, but what do the people that are part of it as a social movement seek to accomplish? According to Miller, “Black Lives Matter’s goals are directly tied to propping up leftist goals and getting leftist politicians into power… I also believe their goals are to abolish the police as they did in the CHAZ/CHOP.” He is referring to the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone/Capitol Hill Organized Protest, where protesters cleared all police out of the area— it was reclaimed by police a few weeks later.

In contrast, in the words of Kanak, “The purpose of the Black Lives Matter movement is to dismantle systemic oppression in the United States by addressing the root of these institutions: racism. Not just deconstructing discriminatory systems, but [also by] making sure they don’t arise later in a different form.”

As for the future of Black Lives Matter, that’s up in the air. One thing’s for sure— it’s certainly gotten people to pay attention. “I would love to say that racism would go away,” says Swirczek. “I would love to say that systemic racism would go away, but it won’t. What I would like to see is support for the black community… I’d like to see more white allies. That’s what we are. We are here to empower the black community. We’re here to give them voices.” Since the Milford protest, she has aimed to do exactly that by co-founding an organization called Talk About It Oakland County. It is centered around providing a place for people to ask difficult questions, which someone might not normally ask for fear of being mislabeled or ostracized. The group also focuses on educating and informing.

Some feel that Black Lives Matter did not entirely miss the mark in its aims, but that it needs to do better. “I hope in the future, both [supporters and non-supporters] can come together and agree on a way to fix the situation for all involved,” states Kotas. “I hope equality is achieved for all, but I also think some things need to be handled in better ways.” Yet others, like Miller, hope that “Black Lives Matter is disbanded and dissolves”. When tasked with the responsibility of directly addressing those that disagree with him, he has only this to say: “Educate yourself before you go argue.”

Antrim, however, has a much different take: “I think my most favorite way I’ve heard it [phrased] is ‘Black Lives Matter too’,” he muses. “I’m a Christian… When I read the Bible, there’s a verse— I can’t think of the exact verse; it’s somewhere in the New Testament— where, you know, Jesus is speaking to his disciples, and he’s talking about all the things that are important, all the virtues that are important to him. And at the very end, he says, ‘But above all, most important is love, and that we love everyone, no matter who they are.’”